This section is dedicated to the ancient and hallowed institution of Trial by Jury — and the Jury Duty service which yielded time to finally put this together

Pulsatile Tinnitus is one of the least understood and most frequently underdiagnosed vascular symptoms. The constant, pulse-synchronous sound can be both alarming and profoundly disturbing. Most patients correctly interpret it as a vascular issue rather than an ear problem. They believe that some kind of abnormal blood flow has begun and are afraid that something may burst inside. As usual, patients are right — it is almost always a blood flow problem. It is completely different from nonpulsatile, constant tinnitus which is usually a high-pitched sound and is often associated with hearing loss. In contrast, pulsatile tinnitus patients usually have normal hearing. Many who are told they have hearing loss simply cannot hear well because the sound interferes with the hearing test. Once pulsatile tinnitus is gone, hearing is magically back to baseline.

What is pulsatile tinnitus? It is a pulse-syncronous sound, more often than not unilateral. It is completely different from nonpulsatile tinnitus. Pulsatile tinnitus is really a bruit. It is a sound usually caused by some kind of abnormal, turbulent blood flow near the ear. There is usually nothing wrong with the ear, which is simply doing its job of hearing sounds. With pulsatile tinnitus, the sound comes from the inside. The challenge is to figure out what is the source of sound.

Various descriptions of the sound are given and in some cases recorded. The most common is a “whoosh” — it is a low frequency sound which is similar to a “baby sonogram.” Some patients are able to record their sound by placing a sensitive microphone into the ear or onto areas of the head, or find a similar sounding recording among the different sounds of cardiac murmurs (like aortic regurgitation). Of course, most cases of PT have nothing to do with cardiac pathology.

Here is a real-life quite severe PT auscultated with a stethoscope on the OTHER side of the sound (sound on right, stethoscope on left mastoid bone). Cause is venous sinus stenosis. The sound is so loud on the right that it drowns out this sound on the left. This is how loud venous stenosis can get. Periods of relative silence correspond to times when the jugular vein is compressed. When compression is released, the sound comes back.

Here is the sound on the “bad” side in the same patient. Same idea — relative silence corresponds to times of jugular compression

Here are a few other sample sounds of Pulsatile Tinnitus, recorded by actual patients. Courtesy of www.whooshers.com

The majority of sounds are unilateral. This is simply because vascular abnormalities which cause PT are usually lateralized. Bilateral sounds can also have vascular etiology, but it is rare.

Many patients report being able to change the volume or pitch of sound by various maneuvers such as neck repositioning, Valsalva maneuver (holding breath and bearing down), or by gentle pressure on the side of the neck.

The last maneuver of gentle neck pressure, which occludes the ipsilateral jugular vein, is particularly important. If the sound stops, it is almost certainly due to venous sinus stenosis or another venous sinus cause, such as dehiscent jugular plate or diverticulum. Venous sinus stenois is by far the most common, and also most under-recognized, cause of pulsatile tinnitus in general and venous pulsatile tinnitus in particular.

It is important to listen with a stethoscope over the ear and mastoid eminence to see if the sound can be heard. Hearing the sound is a near certainty that a cause will be found. However, it is important not to put to much emphasis on “objective” pulsatile tinnitus. “Objective” means that someone other than the patient can hear the sound. However, there are many pitfalls. Most importantly, just because the sound is not heard does not mean it is not real or significant. Perhaps it is too faint to be heard. Perhaps you need a better stethoscope. Or listen in the right place. Finally, it is entirely possible that your own hearing is not what it used to be… So, when “objective” pulsatile tinnitus is present, that is helpful. Lack of objective pulsatile tinnitus — subjective pulsatile tinnitus — does not mean anything. Could still be a dural fistula, venous stenosis, etc. Whether objective or subjective, pulsatile tinnitus is significant and warrants a thorough evaluation

How do we approach pulsatile tinnitus? First, it is key to validate the patient’s likely already formed conclusion — that their sound is different from a constant pitch. That it has to do with blood flow. Yes, it does. Is it dangerous? Maybe, but usually not. For most doctors, that’s a surprise. Yet, it is true. Most PT cases are benign. However, a large minority are not and need a prompt workup.

So, what is the approach? Ask to describe the sound. What makes it better/worse. Is it truly in sync with the heartbeat? Does it increase in frequency with exercise? Can they count the number of beats per minute? Is it the same as the pulse frequency? Can they stop the sound by neck compression (venous sinus stenosis)? Is there neck pain (dissection?). Do they feel dilated pulsing vessels behind the ear (dural fistula)? Was there recent major trauma (carotid fistula)? Are there headaches or vision changes (intracranial hypertension?) Any new medications? Particularly new or different oral contraceptives / hormone replacement (intracranial hypertension again). Is there a heart valve problem (major aortic regurgitation for example)? General hyperdynamic state (hyperthyroidism, major anemia, etc)?

Now, here is the disclaimer for the patient (and doctor). None of the above can be used to diagnose or treat any disease in isolation. Just because someone has neck pain and pulsatile tinnitus does not mean they have carotid dissection. A full evatuation and usually imaging is required.

What about imaging? Imaging is essential. We need to look inside for the source of sound. The approach is geared towards vascular causes. We start with contrast brain MRI (volumetric postcontrast T1 images are as good as an MRV), Time of Flight (TOF) brain MRA, and neck MRA (contrast is better). An MRV can also be obtained however high quality contrast MRI is just as good. What about CTA? I prefer MRA. The problem with CTA in pulsatile tinnitus is that one of the main conditions we are thinking of is a dural fistula. A badly timed CTA (with venous contamination) makes dural fistula more difficult to diagnose. TOF MRA does not have this problem. Also, CTA comes with both radiation and nonionic contrast. MRA does not.

Other studies? A temporal bone CT can be useful also (vascualar variants such as aberrrant carotid, persistent stapedial, etc). What about catheter angiography? The truth is that most of the time, catheter angiography is not necessary. Most causes can be seen on a good set of MR imaging studies. Having said that, catheter angiography remains the gold standard for vascular imaging and is very useful in many circumstances. A well-known association between venous sinus stenosis and intracranial hypertension exists. Patients suspected of it should have an ophthalmology evaluation for papilledema and, frequently, a lumbar puncture to definitively prove or disprove intracranial hypertension. It is wrong however to think that all patients with sinus stenosis have IH. Most do not. And in a good number that do, pulsatile tinnitus is the only symptom — not headaches or vision issues. This may come as a surprise, but IH does not always have to present with headaches. In fact, that’s what makes it more difficult to diagnose.

One very useful way of thinking about PT is separating the uncertainly of what the sound represents (lack of diagnosis) from the impact of the sound per se. Is the patient more bothered by not knowing what causes the sound or by the loud and disturbing nature of the sound itself? In most cases, once the cause is found, the patient can be reassured that the cause is not dangerous. Many patients are then able to cope with such sounds if cure is impractical or felt to be too hazardous. Others, particularly with high volume, constant PT, look for a cure even if the cause is not hazardous. The disturbing and disruptive nature of the sound is enough. For example, venous sinus stenosis is usually benign but occasionally very loud. Cure is possible (stenting) and to those who understand the risks and benefits this approach is very reasonable.

Over the years, we have seen hundreds of patients with pulsatile tinnitus. We have also seen something quite incredible — the definitive role of a patient support group in educating physicians about the true nature and proper workup of pulsatile tinnitus. The sad reality is that 10 years ago most physicians, including ENT specialists, had no idea of the difference between pulsatile and nonpulsatile tinnitus. Patients with obvious vascular conditions were (and sometimes still are) told that they have an ear ringing problem and nothing could be done. Or they were told to wait six months before starting with any diagnostic imaging, to essentially “wait and see” if the sound went away. Pulsatile tinnitus rarely goes away on its own. Many patients are mistakenly told to ‘live with it,” prior to a thorough workup or even beginning one. Unfortunately, most of us did not learn about pulsatile tinnitus in medical school. Or about nonpulsatile tinnitus either. In absence of education, care is usually anecdotal, heterogeneous, and inadequate.

About 10 years ago a pulsatile tinnitus sufferer started a web page www.whooshers.com which quickly became a magnet for fellow sufferers without answers and without support. Over the years, this matured into an online community with a robust Facebook presence, periodic meetings, advocacy to change CPT codes to distinguish between pulsatile and nonpulsatile tinnitus, contacts with medical societies across the globe, etc. Probably more than anyone else, “Whooshers” has served to appropriately educate pulsatile tinnitus sufferers to in turn educate medical professionals about the vascular nature of pulsatile tinnitus. Stories of patients being misdiagnosed for years are becoming rare.

How can a physician systematically approach pulsatile tinnitus differential diagnosis? One way is to think in terms of vascular anatomy.

- Arterial causes include vascular stenoses such as carotid dissection, fibromuscular dysplasia, or atherosclerosis.

- Venous causes are venous sinus stenosis (most common cause, sound usually on side of bigger sinus), and occasionally diverticula, high jugular bulbs, lateral wall dehiscene, and a few others. Intracranial hypertension also falls into the venous category since the sound is made by venous sinus stenosis associated with intracranial hypertension.

- Next come arteriovenous shunts — the famous dural fistula. It is perhaps the most well known but certainly not the most common cause of PT. Too many patients are told that since there is no dural fistula nothing more can be done to find the cause. This is not true.

- Miscellaneous other causes — hypervascular masses such as glomus tympanicum or glomus jugulare. Hypervascular states such as hyperthyroidism. Superior Semicircular Canal Dehiscence. Meniere’s disease.

- Unclear reasons — the reality is that even after an extensive workup and multiple expert consultations, a sizable minority of patients (up to 20% I believe, but this number is a reflection of practice and referral patterns) still has no identified cause. Many of these patients have some degree of real hearing loss. Their sounds are more often bilateral and varied — not a simple whoosh, but periodic sounds that change in pitch, volume, and character. Some will be proven to be periodic but not pulse-synchronous. Others are truly pulsatile. Many are deeply frustrated and depressed. There is no set answer. Medications / supplements are usually ineffective. Management strategies include addressing consequences of the sound — for example how to deal with lack of sleep. Over the counter Melatonin is a good start. Other medications and strategies are possible in consultation with a sleep specialist.

Pitfalls — rhythmic nonpulsatile tinnitus is one. It is a periodic sound that is not in sync with the heartbeat. It can certainly be profoundly disturbing and require treatment. However, it is not vascular and this is key in that vascular workup is going to be useless. How to differentiate between true PT and this one? Count the number of sounds per minute and compare with pulse frequency. If the sound is off by more than a few beats it should raise suspicion of periodic, nonpulsatile tinnitus. Most patients can tell if their sound is exactly in sync with the heartbeat — it varies with exertion just like the heart, occasionally skips a beat when the heart does, etc. The most well-known periodic, nonpulsatile tinnitus is “Middle Ear Myoclonus”. It is caused by myoclonic contractions of muscles related to the middle ear — tensor tympani or stapedius. These can be heard by another person and so it is also in the differential diagnosis of “objective tinnitus”. Palatal myoclonus is also another cause. Treatment is with Botox injections of responsible muscle or surgery.

It is impossible to fully describe the range of symptoms, conditions, and other nuances of how to diagnose and treat PT. However it is important to know that in most cases an underlying cause can be identified. Below is a representative collection of different cases of pulsatile tinnitus. If you are a patient, it is very important to understand that the conditions shown below may be very rare, often do not cause pulsatile tinnitus (though in the following instances they did), may have other symptoms as part of the problem, etc. The purpose of this page is not to encouarage self-diagnosis. It is to show, primarily to medical professionals, the range of conditions and associated imaging findings of patients with pulsatile tinnitus.

Below is a list of some cases. It is by no means a complete list. It is being updated as time and new information allows.

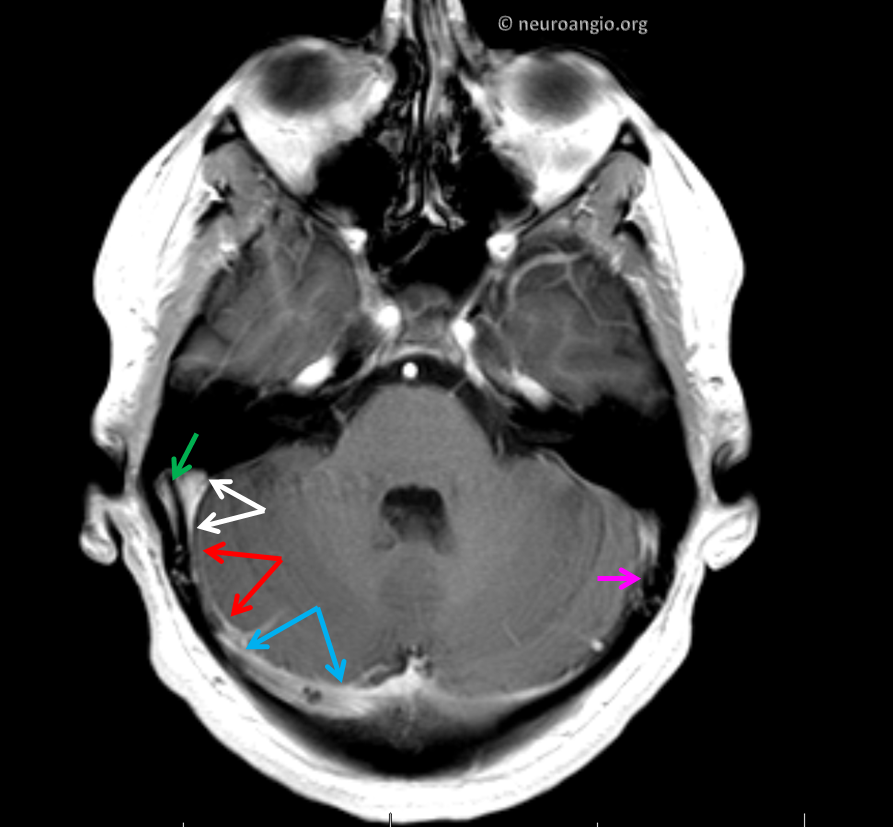

Venous Sinus Stenosis, Imaging Findings

Venous Sinus Stenosis and Sinus Stenting, Case 1

Venous Sinus Stenosis and Sinus Stenting, Case 2 — including normalization of overall cerebral venous drainage

Venous Sinus Stenting, Threatened Labbe Occlusion Rescue

Venous Sinus Stenosis, Intracranial Hypertension, and Sinus Stenting

Venous Sinus Stenosis Despite Prior Ventriculoperitoneal Shunting, Sinus Stenting

Venous Sinus Diverticulum Stenting

Jugular Plate (lateral wall) Dehiscence

Cervical Jugular Compression C1 Lateral Mass Resection and Styloidectomy

Sigmoid Sinus Dural Fistula, Case 1 — vein-sparing approach

Sigmoid Sinus Dural Fistula, Case 2 — pulsatile tinnitus resolves while fistula gets worse

Sigmoid Sinus Dural Fistula, Case 3 — superselective transvenous embolization

Sigmoid Sinus Dural Fistula, Case 4 — superselective transvenous embolization

Superior Semicircular Canal Dehiscence

Links and Literature

There is a lot of literature on PT — most of it is quite good. It is impossible to list everyone. Different authors / groups approach PT from different perspectives, which are in turn influence by local practice patterns and group specialty. This for example influences their perception of what are common and rare causes of PT. We are no exception to this. For example, we see a lesser cross-section of patients with well-known causes such as Dural Fistula. The reason is that many patients come to us for second, third, and Nth opinion, having seen a range of prior specialists. In this setting, the “usual suspects” have already been identified and so the overall population is enriched in lesser known causes. Which is why we emphasize venous sinus stenosis as the most under-diagnosed cause today, in our opinion.

Aside from scientific literature, there are a number of useful links on the web, but the overall spectrum is very heterogeneous and genuine caution is advised when surfing the web without a healthy sense of doubt

Useful Links

www.whooshers.com — premier support and information center for pulsatile tinnitus. Check out their facebook page as well

https://www.tinnitus.org.uk/pulsatile-tinnitus — British Tinnitus Association

Ukrainian Version of 10 TIPS FOR PHYSICIANS

Literature – a sample only