Patient Information Spinal Metameric (Juvenile) AVM

This page is intended as a source of information for patients suspected of or having been diagnosed with a spinal intradural fistula. Please remember to read the “Disclaimer” section — none of this information may be used to diagnose or treat any disease. This is for general information purposes only.

Should you need more information, or if you are a patient wishing to make an appointment, you can write to me directly or call the office, both of which are listed in the “Contact Us” section. Our group at the NYU Langone Medical Center is one of the premier neurointerventional centers in the world.

Overview

An AVM, or arteriovenous malformation, is an abnormal connection between arteries and veins through a disorganized tangle of small curvy vessels called the “nidus”. Normally, blood travels in a predictable route from large to progressively smaller arteries to very small vessels called capillaries, where oxygen and nutrition are delivered and waste picked up, and from there goes on to venules and veins. Occasionally, a short circuit exists when blood bypasses the capillaries (and therefore normal tissue) and goes directly from arteries to veins. One such short circuit is an AVM. Any part of the body can have an AVM (brain AVMs are one example). One can also have an AVM which involves the spinal cord. When it only involves the spinal cord, the condition is appropriately called “Spinal AVM”. However, an AVM can be more complex, and in addition to spinal cord may also involve the covering of the cord (called the dura) and other adjacent structures such as bone or muscle. This kind of large, complex AVM is called “Spinal Metameric AVM”. The “metameric” part refers to the fact that our bodies are, fundamentally, made in segments or blocks. For example, each pair of ribs, the vertebral bone they are attached to, adjacent muscle, fat, skin, and a piece of spinal cord at that level are built from one segment of embryonic tissues. Another word for segment is “metamere”, and from that comes the term “metameric”. Sometimes, these are also called Spinal Juvenile AVMs — a misleading term suggesting that the disease has something specific to do with “Juvenile” years. It is an older name which was given to the disease because many patients first developed symptoms and were then diagnosed in their juvenile years. However, the AVM itself is present from birth, usually in a small form. It grows along with the patient, not like cancer, but slower and without possibility of distant spread.

Symptoms

Even large AVMs can have no symptoms (as they are in majority of children), but eventually issues do develop in most patients, usually in their teens or early twenties. The problems are usually due to two major types of events: bleeding and ischemia.

Because the vessels making up the AVM are abnormal in many ways, they are prone to bleeding. Bleeding can come from many places: the arteries feeding the AVM, the nidus itself, or the venous outflow. AVMs have propensity to develop aneurysms (enlargements and balloonings of the vessel wall) and areas of vessel stenosis (narrowing), both of which can lead to bleeding. The consequences of bleeding depend on location and extent of the bleed.

Ischemia refers to a state of insufficient supply of oxygen to the spinal cord. This happens chiefly because the AVM “steals” blood away from adjacent spinal cord and nerves. Venous hypertension can also cause problems.

Other issues can arise depending on the anatomy of the AVM, but they are relatively less important than problems having to do with the spinal cord.

Symptoms

Because AVMs can involve any location along the spinal column and produce a host of different problems, the symptoms are extremely variable. Pain, numbness, weakness, loss of bowel/bladder control, incoordination, and impotence are some of the issues. It is very difficult to make a diagnosis of an AVM based on symptoms alone.

Diagnosis

In the era of modern imaging, the diagnosis is almost always established by MRI. Because of their large size and very abnormal appearance, spinal AVMs are quite easy to visualize on MRI, with our without contrast. Apart from diagnosis, MRI can be invaluable in defining the extent of spinal cord vs. adjacent involvement by the AVM. Continued refinement of MRI technology has made some positive difference in management of spinal AVMs.

Another noninvasive method of diagnosis is by CT scan (contrast is very helpful in these cases). CT myelography can also visualize the large vessels surrounding the spinal cord.

Spinal Angiography

The next step in evaluation of spinal AVM is catheter spinal angiography. During angiography, a skinny but long catheter is inserted (usually from a large artery in the leg) under x-ray guidance into many vessels giving rise to the AVM and adjacent normal segments, visualizing the arteries and veins during injection of contrast. Spinal angiography gives by far the most detailed and dynamic information about the vessels making up the AVM. It is a long procedure which requires the patient to be completely motionless and therefore is almost always done under general anesthesia (completely asleep). Sometimes, angiography may not need to be done (if the diagnosis is already clear and no intervention/treatment is being planned).

Additional Testing

Other tests may be necessary depending on the situation, such as urodynamics (a study of how the urinary bladder fills and empties), EMG (electromyography), nerve conduction studies, and evoked potentials (to evaluate possible nerve damage) among others.

Disease Course and Treatment

Overall, medical literature on metameric spinal AVMs is rather pessimistic. Many patients eventually develop significant neurologic dysfunction, meaning weakness, sensory abnormalities, problems with urine/bowel control, pain, etc. It is important to realize, however, that even such formidable lesions as metameric AVMs have a lot of variety and some can run a relatively benign course. Much depends on the exact location and anatomy of the AVM.

The vast majority of metameric AVMs cannot be cured because of their complexity and involvement of the spinal cord, where radical treatments would mean a very high chance of paralysis or some other profound neurologic dysfunction. On the other hand, a strategy aimed at addressing particular more troublesome parts of the AVM can be quite successful. In other words, a thoughtful conservative approach is often better than an all-out assault.

Treatment options consist essentially of various endovascular embolization techniques. Similar to a spinal angiogram, a catheter is introduced into a vessel. Through this catheter, a smaller thinner catheter or catheters are guided to the desired area, and the problem spot plugged up either by a glue-like substance or sometimes with small plastic spheres or small metal coils. If the bone is extensively involved, or if fracture or pain develop, this can also be addressed by surgical means. In very limited cases under very favorable conditions, a complete cure can be attempted usually by combination of embolization and surgery.

In practice, most metameric AVMs are best managed by a team approach. This is a long-term condition requiring coordinated care by specialists from neurology, neurosurgery, and neurointerventional radiology. Particularly important is the role of a rehabilitation specialist and a physical/occupation rehabilitation team, which can make a huge difference in functional capacity of the patient. Expert care by specialists in psychiatry and psychology can also be immensely helpful for both patient and loved ones in dealing with the heavy emotional burden and motivating the patient to achieve the best possible functional outcome.

Our role

Our Neurointerventional Radiology group specializes in performance of spinal angiography and transcatheter (endovascular) embolization of spinal vascular malformations. We are located at the NYU Langone Medical Center, in New York City. As all centers of excellence, we function as part of a team of neurosurgeons, neurologists, rehabilitation specialists, psychiatists, and diagnostic radiologists, all of whom have extensive experience with vascular conditions of the spine. Regardless of where you may seek medical advice, we STRONGLY recommend that your evaluation and management be carried out at a major center with extensive experience in treatment of this condition, as details of diagnosis and therapy can be extremely complex. A small number of excellent centers for this condition exist accross the US and elsewhere.

Imaging

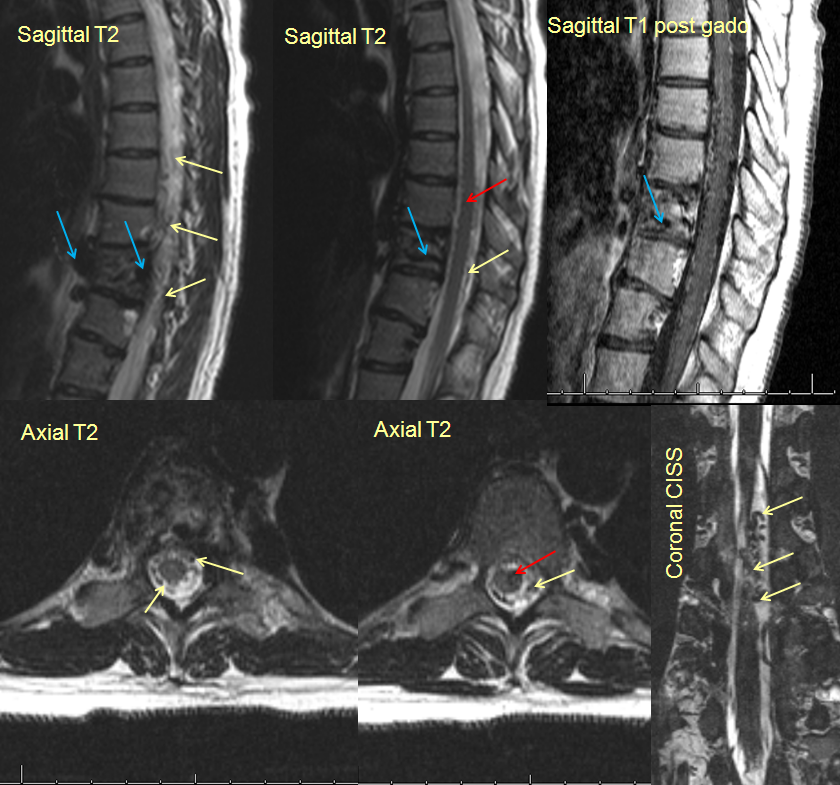

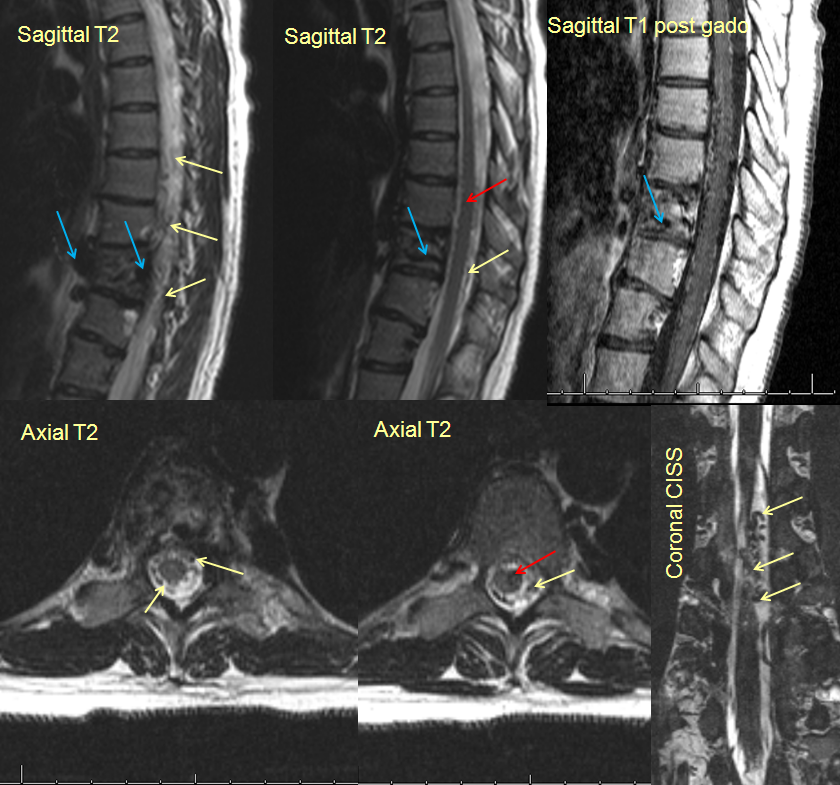

Below are some MRI images of a patient with a metameric spinal AVM. The midline (sagittal) and transverse cut (axial)images show involvement of the vertebral body (blue arrows), the surface of the spinal cord (yellow arrows) and spinal cord itself (red arrows), all part of a body segment, a typical Spinal Metameric AVM.

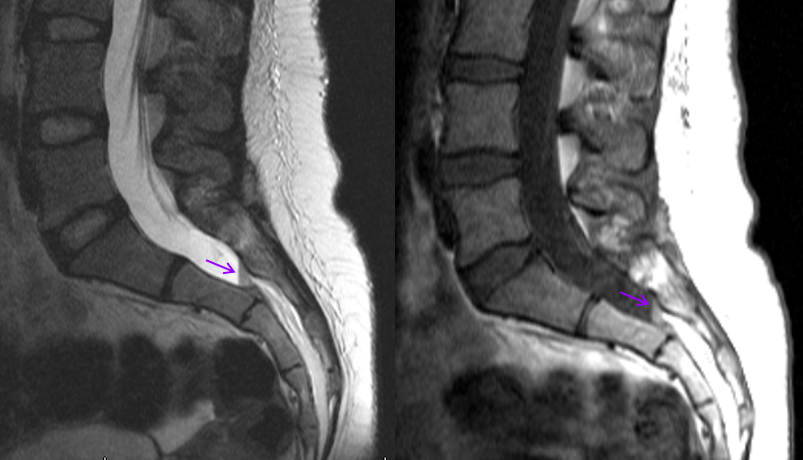

Midline images of the lumbar spine (bottom of the spinal canal) show a straight line (purple) representing a fluid-fluid level. This is a small amount of blood which leaked out from the AVM and collected at the bottom of the spinal column. The patient presented with pain and numbness in the legs.

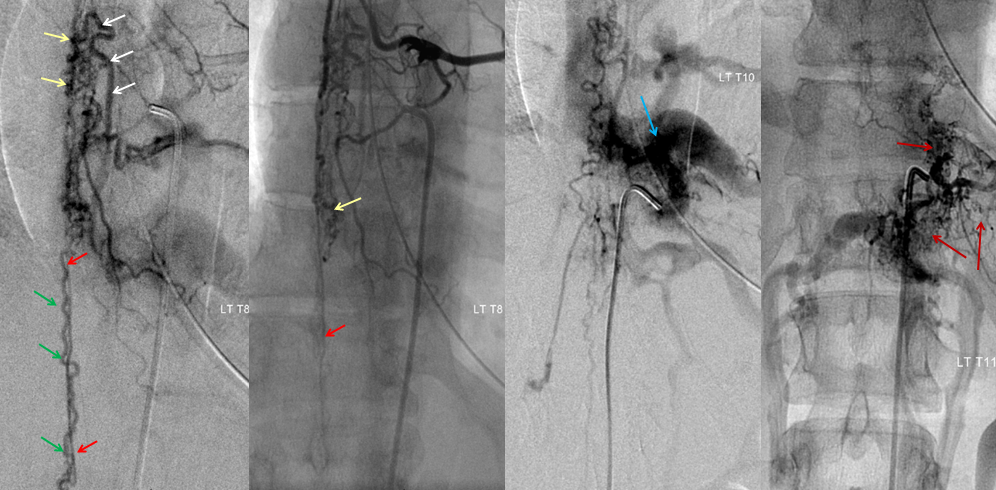

Catheter spinal angiogram of the same patient, showing markedly dilated radiculomedullary artery (white) supplying a pathologically enlarged anterior spinal artery (red) decompressing into a spinal vein (green) and extensive additional pial (cord surface) and intramedullary (within the cord) vasculature (yellow arrows). Injection of adjacent levels shows involement of the vertebral body and adjacent soft tissues (blue and brown arrows)

Contacting Us