The purpose of this page is to acquaint the reader with techniques and common indications for spinal angiography. Discussion is geared towards health professionals and knowledgeable laymen. Additional information, more immediately patient-centered, is found in the Patient information Section dealing with conditions of Spinal Dural Fistula, Spinal Metameric AVM and others.

What is spinal angiography? Similar to angiography of the brain, where a catheter is placed into an artery supplying the brain parenchyma, such as internal carotid or vertebral artery, and contrast material injected to directly visualize brain arteriovenous system, — spinal angiography accomplishes the same goal for arteries which supply the spine and paraspinal regions. There are usually 31 vertebrae in the body, and most have 1 or 2 individual arteries feeding them. Which means that spinal angiography can be a long procedure, if the entire spine vasculature needs to be visualized. That is not always the case. However, because of the length of procedure, and because the arteries and veins of the spine tend to me much smaller than of the brain, spinal angiography is usually done under anesthesia. This minimizes movement of the patient, which degrades imaging, and allows for control of breathing and peristalsis (movement of the bowel). The less movement, the better. The procedure is as follows: the patient is placed under anesthesia, a catheter is introduced into the aorta, usually via the artery in the groin called femoral artery, and various catheters are used to individually catheterize spinal arteries, one by one, taking x-ray pictures of each. Depending on the disease process, several or dosens need to be viewed. Once angiography is completed, the catheter is withdrawn, groin access site closed by compression or deployment of special closure devices, and patient woken up. Sometimes, both angiography and actual treatment of the condition in question can be carried out at the same time.

Spinal angiography is more specialized than even brain angiography. Many places which are comfortable with brain angiography may not be as versed in spinal procedures, depending on disease. For example, in our very busy Neurointerventional Center, with special emphasis on spinal angiography, about 30 are done each year, compared with upwards of 1,000 brain angiograms.

Indications for Spinal Angiography — why do it?

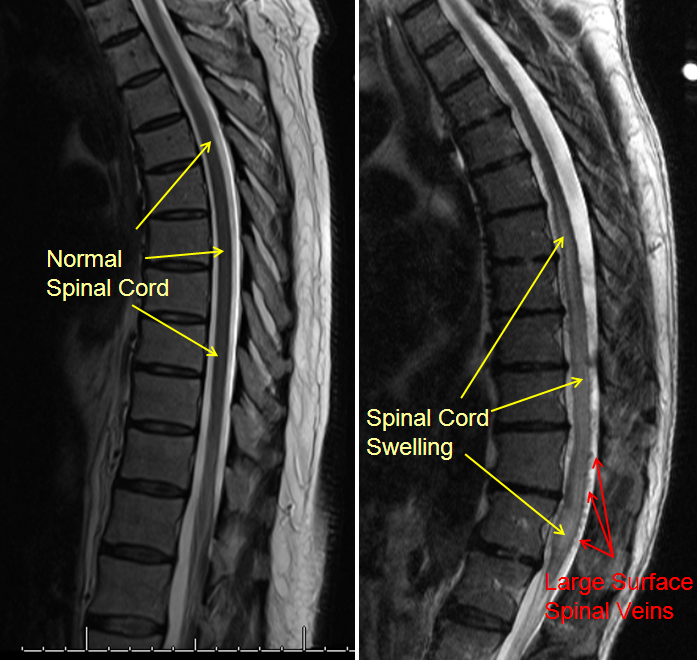

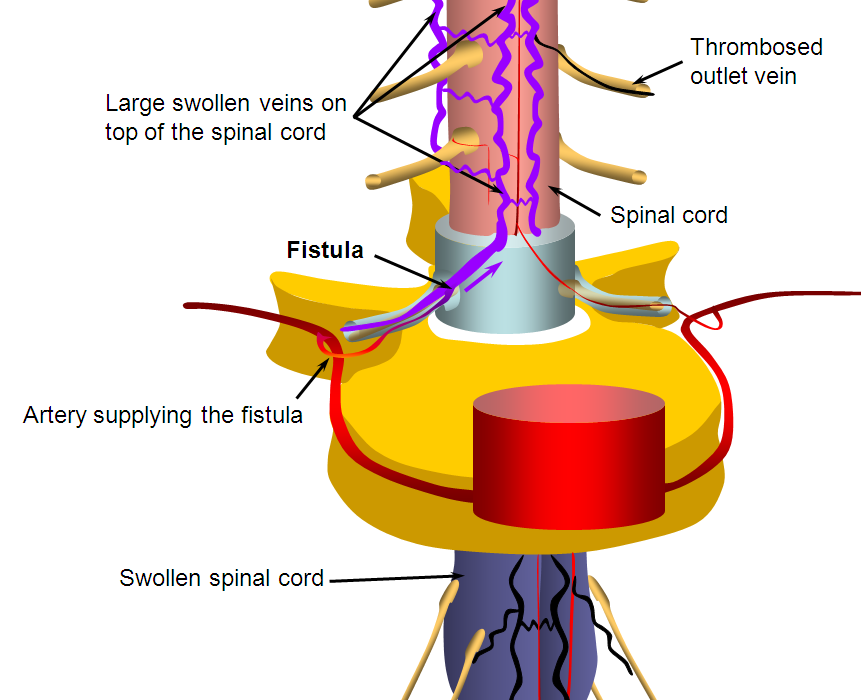

1) Suspected Spinal Dural Fistula. This is the most common arteriovenous disorder of the spine — an abnormal direct communication between artery (usually within the nerve root sleeve) and a nearby vein, producing spinal cord venous congestion and eventual dysfunction, leading to paralysis, bowel/bladder problems, bleeding, etc. Other, even less common fistulas, such as the pial kind, are also occasionally seen. The diagnosis of spinal fistula (dural or pial) is usually suspected based on MRI imaging, which shows many enlarged veins in the spinal canal adjacent to the spinal cord, and spinal cord edema/atrophy. With these findings, a fistula or some other vascular disorder of the cord is almost certain. MRI cannot, however, see the actual fistula, or treat it. When a fistula is suspected, the next test is spinal angiography. There are at present time no reliable alternatives to spinal angiography for this disease, although special MRA techniques are becoming practical at specialized centers with the necessary dedication and attention to detail. Treatment of the fistula can be carried out via embolization at the same time as spinal angiography, or later. Sometimes, the level of suspicion for dural fistula is not so high, but angiography is nevertheless requested after multiple other tests fail to yield a diagnosis in a deteriorating patient. For detailed information, see Patient Information Spinal Dural Fistula, Cases Spinal Dural AV Fistula, and Spinal Vascular Anatomy.

2) Other arteriovenous disorders of the spine. More rare, but usually more sinister conditions, such as spinal metameric (juvenile) AVM. Usually there is no question that spinal angiography is needed. Effective treatment is more of a problem.

3) Spinal tumor embolization. Tumors affecting the bone (vertebrae) and other tissues adjacent to the spine, are sometimes suspected to be very vascular. Common offenders include renal cell carcinoma, melanoma, hemangioma. Their resection can be associated with copious blood loss and surgical difficulties. Pre-operative embolization of the mass, usually with particles, is performed to decrease vascularity and facilitate resection.

4) Spinal stroke. Relatively uncommon condition, and rare indication. Suspected rarely, it may be useful to perform spinal angiography to document occlusion of spinal artery (almost always the artery of Adamkiewicz, though rarely vertebral artery dissections can produce devastating cervical spinal infarcts); more typically, however, spinal infarct emerges as conclusion at the end of angiography requested for another suspected diagnosis.

5) Unexplained spinal disease. Occasionally, we are referred a diagnostic enigma patient, where most tests have been inconclusive, and somebody raises the possibility of an occult vascular disorder, for which spinal angiography is the next step. In such cases, a diagnosis may in fact be made after spinal angio. However, since spinal angio is neither quick, nor cheap, nor risk-free, determination as to need is made on individual basis, following direct patient consultation.

Questions / Referrals: For questions, or to refer a patient for spinal angiography consultation, you can contact us using the Contact Us page or calling the office (phone in contact page section)

Images:

Typical MRI appearance of spinal dural fistula, with normal MRI on the left, and spinal fistula MRI on the right, demonstrating multiple enlaged veins surrounding a swollen spinal cord. This is a classic: there is nothing else that produces this picture. If you see this, spinal angiogram is the next diagnostic study.

Diagram of the fistula as a direct connection between nerve root sleeve artery and spinal veins.

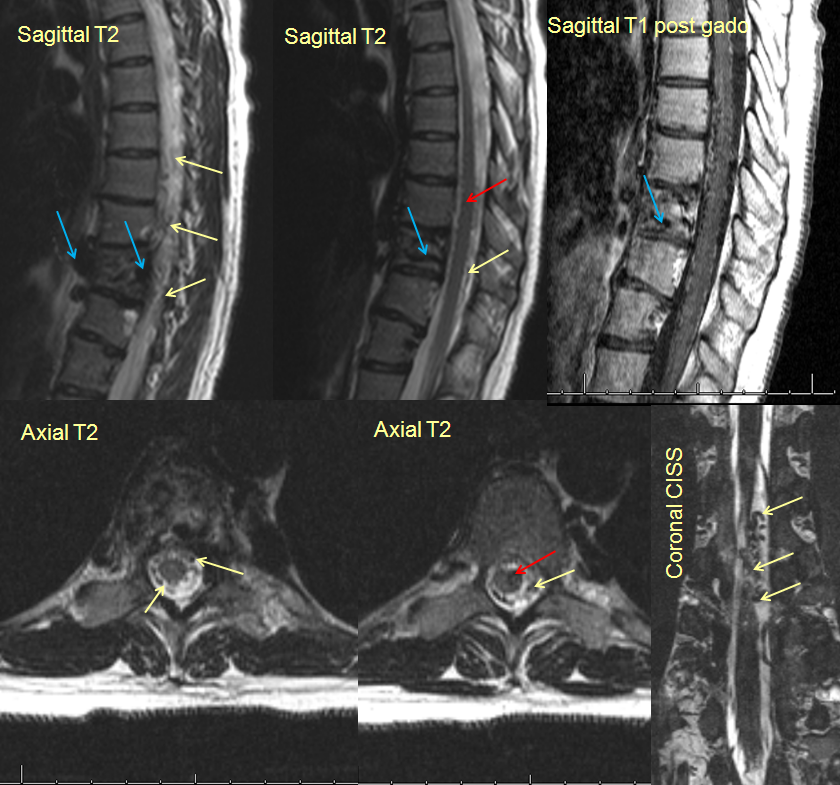

MRI appearance of spinal metameric AVM, a rare condition with large AVMs affecting spine and paraspinal tissues. Arrows point to different components of the AVM, described in the spinal metameric (juvenile) AVM section.

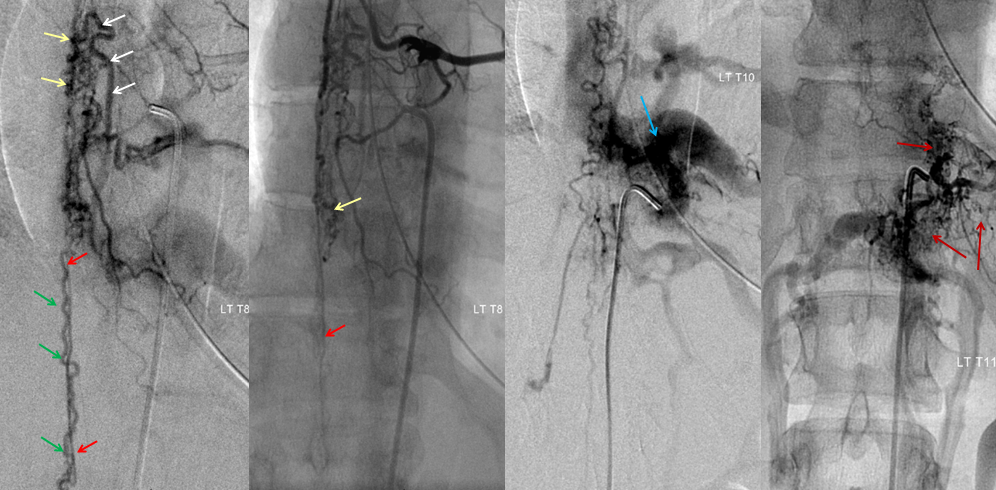

Catheter angiogram of the same AVM

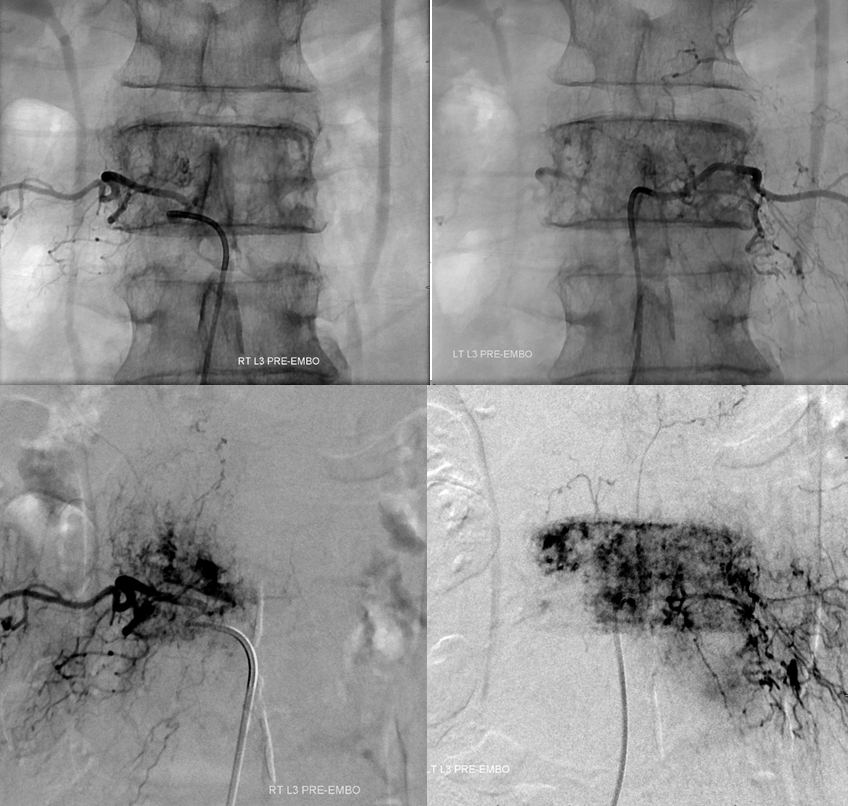

An L3 level (lumbar spine) hemangioma, causing pain and radiculopathy due to compression of the spinal nerve roots (extensive epidural component), pre-embolization MRI and angiogrpahic images.

Right and left L3 segmental artery injections, showing hypervascularity within the L3 bone.